Where Were Most Upper Paleolithic Cave Art Sites Found?

Rock art (besides known as parietal art) is an umbrella term which refers to several types of creations including finger markings left on soft surfaces, bas-relief sculptures, engraved figures and symbols, and paintings onto a rock surface. Cavern paintings, above all forms of prehistoric art, have received more attending from the academic inquiry community.

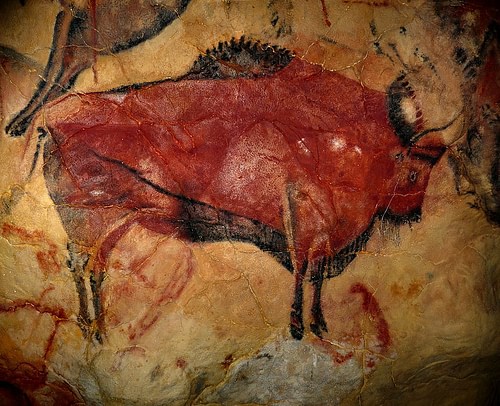

Paleolithic Cavern Painting in Altamira Cavern

Stone art has been recorded in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Commonwealth of australia, and Europe. The earliest examples of European rock art are dated to about 36,000 years ago, but it was not until around 18,000 years ago that European rock art really flourished. This was the time following the cease of the Last Glacial Maximum (22,000-19,000 years agone) when climatic conditions were start to improve subsequently reaching their about critical point of the Ice Historic period. Upper Paleolithic rock fine art disappeared of a sudden during the Paleolithic-Mesolithic transition period, effectually 12,000 years ago, when the Ice Historic period environmental conditions were fading.

It has been suggested that in that location is a correlation betwixt demographic and social patterns and the flourishing of rock art: In Europe, the rock art located in the Franco-Cantabrian region (from southeastern France to the Cantabrian Mountains in northern Spain) has been studied in great detail. During the tardily Upper Paleolithic, this area was an platonic setting for prolific populations of several herbivorous species and, consequently, a high level of human population could be supported, which is reflected in the affluence of the archaeological textile institute in the region. Nevertheless, in contempo years the geographic region in which Upper Paleolithic stone art is known has increased significantly.

Afterward over a century of give-and-take about the 'significant' of rock art, no complete scholarship consensus exists, and several explanations take been proposed to account for the proliferation of this prehistoric art. What follows is a brief summary of some of the explanations that have been put forward to account for the significant of European Upper Paleolithic rock art.

ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDIES WORLDWIDE Normally EMPHASIZE THE RELIGIOUS/SPIRITUAL ORIGIN OF ROCK ART.

Art for Art'south Sake

This is possibly the simplest of all theories about Upper Paleolithic stone art. This view holds that there is no real significant behind this blazon of art, that it is cipher but the production of an idle action with no deep motivation behind information technology, a "mindless decoration" in the words of Paul Bahn. As simple and innocent as this view may audio, information technology has some important implications. Some late 19th- and early 20th-century scholars saw people in the Upper Paleolithic communities every bit brute savages incapable of beingness driven past deep psychological motivations, and they fifty-fifty rejected the thought that rock art could accept any connection with religion/spiritual concerns or any other subtle motivation. This arroyo is not accepted today, simply information technology was an influential 1 in the early years of archaeology.

Cave Painting in the Altamira Cave

Boundary Markers

Some scholars take claimed that rock art was produced as boundary markers by unlike communities during the time when climatic conditions increased the competition for territory between Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherer communities. Cave fine art, according to this view, is seen as a sign of the ethnic or territorial divisions within the different Upper Paleolithic homo groups coexisting in a given area. Cave fine art was used as a marker by hunting-gathering communities in social club to point to other groups their 'right' to exploit a specific area and avoid potential conflicts. Michael Jochim and Clive Chance have made very similar arguments: they proposed the idea that the Franco-Cantabrian region was a glacial refugium with such a loftier population density during the Upper Paleolithic that fine art was used equally a social-cultural device to promote social cohesion in the face of the otherwise inevitable social conflict.

This argument is in line with demographic and social patterns during the Upper Paleolithic. More population density meant more than competition and territorial sensation. However, this model has some flaws. Hatfield and Pittman note that this approach is not consistent with the stylistic unity displayed by some rock art traditions. David Whitley has observed that this statement is not but filled with a dose of 'western bias.' only information technology besides contradicts the fact that no ethnographic report provides back up for this claim. It could also be said that if Upper Paleolithic groups increased their awareness of territoriality, it is reasonable to await some sort of indication of this in the archaeological record, such as an increase of signs of injuries inflicted with precipitous or blunt weapons in homo remains, or other signs of trauma that could be linked to inter-group conflicts. Although in this case it is possible that if the art actually helped to avoid conflict, no such signs would be detected.

Structuralist Hyphothesis

By analyzing the distribution of the images in different caves, André Leroi-Gourhan suggested that the distribution of the cave paintings is not random: he claimed in that location is a structure or pattern in its distribution, sometimes referred to equally a 'design'. Most horses and bison figures were, according to Leroi-Gourhan'due south studies, located in central sections of the caves and were also the about arable animals, about lx% of the full. Leroi-Gourhan added that bisons represented female and horse male identity. He argued that some unchanging concepts relating to male and female identity were the footing of rock art. In the words of Paul Mellars:

Paleolithic art might be seen as reflecting some fundamental "binary opposition" in Upper Paleolithic society, structured (perhaps predictably) around the oppositions between male and female person components of society (Mellars, in Cunliffe 2001: 72).

In add-on to studying the figurative art, Leroi-Gourhan besides paid attending to the abstruse motifs and tried to explain them inside the context of the structuralist idea that was ascendant during his time in linguistics, literary criticism, cultural studies, and anthropology, peculiarly in France. Structuralist thought claims that man cultures are systems that can exist analyzed in terms of the structural relations among their elements. Cultural systems incorporate universal patterns that are products of the invariant structure of the human mind: proof of this tin can be detected in the patterns displayed in mythology, art, religion, ritual, and other cultural traditions.

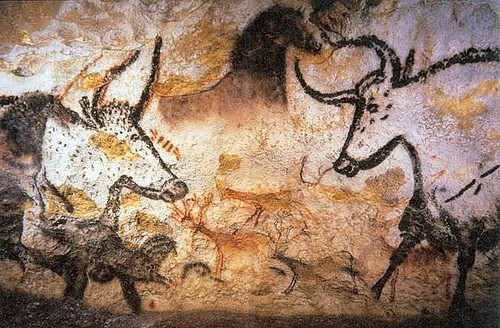

Cave Paintings in the Chauvet Cave

Initially, this explanation was very popular and widely accustomed by scholars. However, when André Leroi-Gourhan attempted to fit the evidence into his standard layout scheme, a correlation could non be proven. It also became axiomatic, as more rock art was discovered, that each site had a unique layout and it was not possible to apply a general scheme that would fit all of them.

Although unsuccessful, the approach of André Leroi-Gourhan was influential. He as well has another important merit: at the time, structuralist thought was dominant in many academic disciplines: by attempting a structuralist caption of rock art, Leroi-Gourhan was seeking to evidence that Upper Paleolithic people were not ignorant savages but were people with cognitive capacity, only like people today.

Hunting Magic

Another suggestion is that Upper Paleolithic rock art is a manifestation of sympathetic magic, designed as an aid for hunting, in the words of Paul Mellars, to "secure command over particular species of animals which were crucially important human nutrient supply". Some supporting evidence of this view includes the fact that sometimes the animals were manifestly depicted with inflicted wounds, coupled with ethnographic illustration based on supposed similarities betwixt Upper Paleolithic fine art and Australian Aboriginal rock art. Magic rituals may not have a direct textile outcome, but this blazon of practice surely boosts the confidence and has a straight psychological do good (a form of placebo effect), increasing the success of hunting activities. In this context, Upper Paleolithic stone art is seen every bit a tool to magically benefit the groups' subsistence, encouraging the success of the hunters.

The ethnographic data indicating that magic plays a meaning part in tribal life does not only come from Australian Aboriginal groups. Other examples are constitute amongst the native Kiriwina people who live in Papua New Guinea, where the levels of superstition and magic ceremonies ascension with the levels of dubiousness: when it comes to canoe edifice, for example, we read that magic

is used only in the example of the larger bounding main-going canoes. The pocket-size canoes, used on the calm lagoon or about the shore, where there is no danger, are quite ignored by the magician (Malinowski 1948: 166, emphasis added).

This emphasizes the thought that magic can be a psychological response to conditions where uncertainty grows, which is what we would look in the case of hunters affected by increasing population pressure.

Shamanism

In this explanation, Upper Paleolithic art is the result of drug-inducing trance-like states of the artists. This is based on ethnographic data linked to San stone art in Southern Africa, which has some common elements with European Upper Paleolithic art.

San rock art

Lewis-Williams has argued that some of the abstract symbols are actually depictions of hallucinations and dreams. The San religious specialists, or Shamans, perform their religious functions under a drug-induced state: going into trance allows them to enter into the 'spirit realm', and it is during this states that shamans claim to see 'threads of lights' which are used to enter and exit the spirit realm. When the human brain enters into certain altered states, bright lines are office of the visual hallucinations experienced past the individuals: this pattern is not linked to the cultural background only rather a default response of the encephalon. Long, sparse red lines interacting with other images are nowadays in San rock paintings and are considered to be the 'threads of light' reported by the shamans, while the spirit realm is believed to be behind the stone walls: some of the lines and other images announced to enter or leave from cracks or steps in the stone walls, and the paintings are 'veils' between this world and the spirit world.

This is another solid argument. Nevertheless, in that location is no basis to generalize the idea of shamanism as the cause of European rock art as a whole. Shamanic practices could exist, at all-time, considered a specific variation of the religious and magical traditions. Shamans do not create magic and religion; instead, information technology is the propensity for assertive in magic and religion nowadays in most every club that is the origin of shamans. Ultimately, this statement rests on magic and religious practices, not far from the argument that sees art as a form of hunting magic.

Conclusion

Since nearly all cultural developments have multiple causes, it seems reasonable to suppose that the evolution of the Upper Paleolithic has a multi-causal explanation rather than a single cause. None of the arguments presented above tin account fully for the development of Upper Paleolithic rock fine art in Europe.

Anthropological studies worldwide commonly emphasize the religious/spiritual origin of rock fine art. This is not the but origin detected through ethnographic studies; there are examples of secular use, but it is apparently the most frequent. However, it could besides exist the instance that fine art in the European Upper Paleolithic had a different meaning from the communities that ethnographers take been able to study. Archaeology has been able to discover caves that may take been connected to rituals and magic at least in some Upper Paleolithic communities of Europe. Human burials were institute in the Cussac cave associated with Paleolithic art: according to some authors, this stresses the religious/spiritual character of the stone art institute in some caves.

Cave Painting in Lascaux

If the assumption that at least some European rock was created for religious reasons can exist accepted, then information technology is condom to suppose that rock fine art is just the most archaeologically visible prove of prehistoric ritual and conventionalities, and unless rock art was the only and exclusive material expression of the religious life of prehistoric communities, we tin assume that there is an entire range of religious material that has not survived. Some of the Upper Paleolithic portable art could also be continued to religious aspects and be part of the 'material package' of prehistoric ritual.

Our noesis about the meaning of Upper Paleolithic rock and portable art should not exist considered either right or incorrect, only fragmentary. The element of uncertainty, which involves the rejection of whatsoever form of dogmatic or simplistic caption, is probable to always be present in this field of written report. This should atomic number 82 to flexible models complementing each other and the willingness to take that, as more bear witness is revealed, arguments will have to be adjusted.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/787/the-meaning-of-european-upper-paleolithic-rock-art/

0 Response to "Where Were Most Upper Paleolithic Cave Art Sites Found?"

Post a Comment